Once you can catch a few seconds freestanding, a metaphysical question enters your handstand life:

To wall or not wall?

After months, sometimes years of hard work conquering your fears, it is only natural to choose the latter… and spend as much time in the middle of the room as possible.

At last, you divorced the wall! The last thing you want to do is to go back to this pesky, soul-crushing tool.

At that stage, you can expect:

Peers to push you to do more freestanding, this is where the fun is after all.

Teachers to push you back to the wall. This is where foundations are solidified.

Finding the in-between, I’m going to propose a balanced approach.

One that ensures that you rip the rewards you’ve been working on while paving the way to your future successes.

One that doesn’t forget about the necessity for our practice to be fun… while ticking all the necessary boxes.

Finally, and maybe even more importantly, one that adapts to the ups and downs of life.

The importance of freestanding

The underrated importance of fun

Freestanding, ie being able to kick-up and hold something in the middle of the room, is not an easy skill to achieve.

If you know what a nervous system somehow resistant to this whole upside-down idea feels like, well you know…

The moment you open that door, it is only normal to reap the fruits of your efforts.

THIS (Freestanding) IS IT.

This is handbalancing.

Sure you will want more: more seconds, more shapes, more straightness…

But everytime you manage to catch a few seconds in the air - you’re doing it.

And it feels great.

The first obvious reason why you shouldn’t whip yourself in the back and go back to the wall is:

deriving fun from, all the more so by achieving the goal of, your practice is essential for long term adherence.

There is a saying among trainers in the fitness world that goes like:

the best program is not the one that will yield the best performances… but the one that the student will adhere to.

You can design a NASA-style program… you will still make better gain by doing 10 push-ups a day for 365 days than going through the best program in the world once and then ditching it.

Take-away: As long as the freestanding part is rewarding (more on this below), you should make sure to include some (or a lot) of it in your training.

The best teacher

Beyond this dopamine aspect of training, we should not forget that being able to catch even a couple of seconds in the middle of the room is an amazing performance where you managed to do EVERYTHING right… albeit “only” for a few instants of elation.

The kick-up technique, your alignment, your finger pushing timing, your small and big corrections, your body awareness, your tension and stillness, your external and internal cues… for it to work, you HAD to do it all pretty well.

Therefore, freestanding is not only to be seen as the prize, but also as the teacher.

Whenever you hold 50% or more of your personal best, that rep is teaching you something.

🤔 Spend a few seconds reflecting on your good reps when you come back down.

📷 Record yourself and analyse the footage.

🧘 And accept that everything won’t be visible - and that a lot of it will be digested subconsciously.

When things are good and your freestanding is working, whether it’s 2 or 30 seconds, roll with it - it has something to teach you.

The importance of the wall

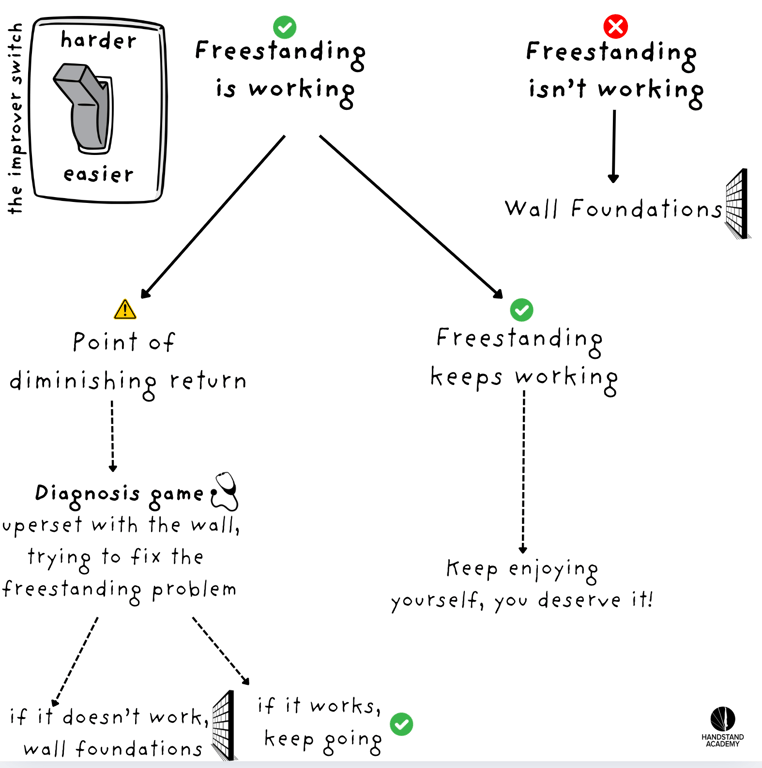

Thing is, two scenarios usually happen to contradict what we said above.

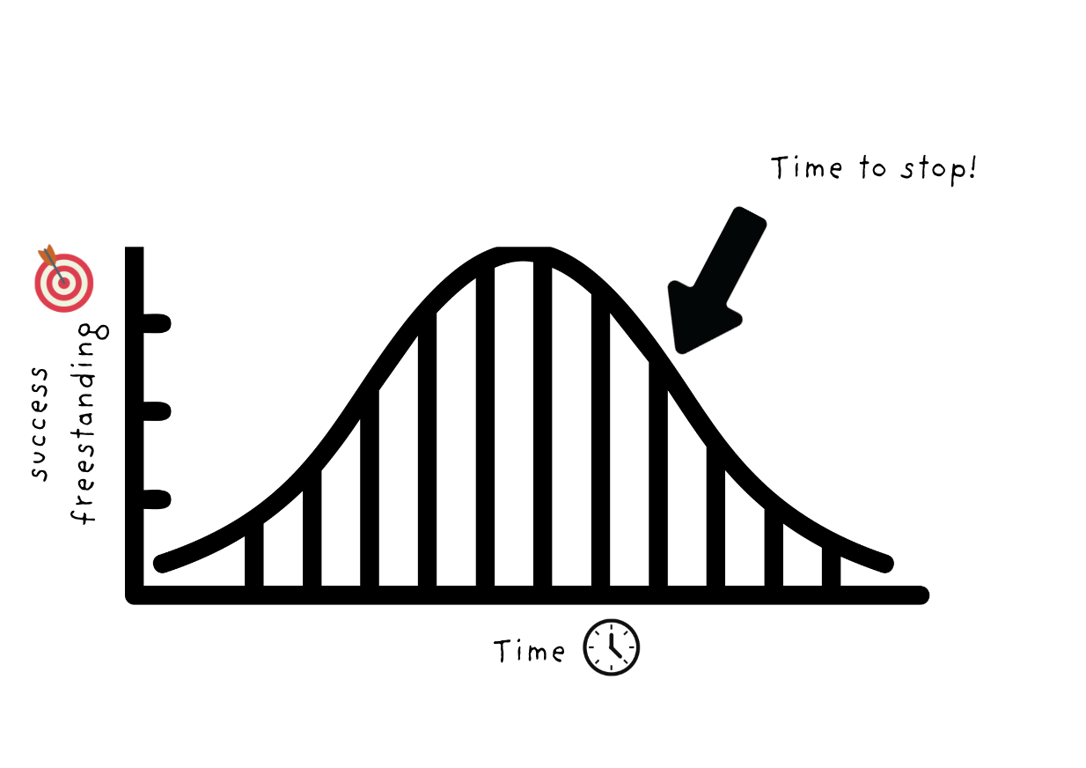

- There is a point of diminishing return.

After a few minutes of freestanding, we suddenly get tired. The worst part: it is usually a form of mental tiredness, that creeps in and starts worsening your consistency rate, your alignment and your duration. The point of diminishing return is usually well behind us by the time we notice it. At that stage, freestanding ISN’T the best teacher any more, and you are greasing a groove of suboptimal technique.

This is a warning sign telling you you should go back to the wall, either for a moment as way to bounce back in your freestanding (diagnosis) or for the remainder of the session (foundations).

- Not every day is a good day

Sometimes the stars won’t align. You won’t catch your usual freestanding handstands. It will either be a struggle to catch half of what is usually easy, or impossible.

This sucks… and is totally part of handstands.

After a decade in teaching this art and science, I only start to realise that this is probably where the depth of the practice is. Reminding us of the impermanence of things, teaching us patience and grit.

You have to make peace with it if you want to last long enough in this game to make peace with it.

When we’re having a not-so-great day, doing the usual amount of freestanding is not advisable. Go back to the wall. Smile, there is no shame with it. You’re better off honing your foundations there, reminding yourself that even the most amazing handbalancers in the world still use the wall sometimes, than spending 45 minutes throwing yourself in the air and finish the session frustrated.

This is a very common trap. We all do it, from the improver level upwards. Do NOT insist on freestanding on a bad day. You will waste a lot of time, suck the fun out of your practices, and rehearse bad technique simply because you held unjustly high expectations on yourself.

My advice: The Difficulty Switch

When I coach people online, I take into account all these parameters, and much more. By the way, they also apply to the beginners, and I will remind them that what is at the periphery of their mastery zone (usually, being able to take off the wall C2W) is something to be hammered on on a good, fresh day, and not to be insisted on when it simply doesn’t want to work.

A mental model I use with them is the difficulty switch: